At –20 °C, Harbin is not a city that yields easily to photography. What began as an architectural photo trip became a quieter lesson in adaptation, winter, and trust in both place and camera.

All photos taken with Pentax K-70 and iPhone 13 Mini.

In northeast China, near the border with Russia, lies a lesser-known megacity shaped by history and geography. After China’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese War and the subsequent Triple Intervention, Russia gained influence over this region and, in 1898, laid the foundations of what would become Harbin. The city was designed by Adam Szydłowski, a Polish engineer working for the Russian Empire, and quickly developed into the central hub for the construction of the Russian-funded Chinese Eastern Railway. Long after the tracks were laid, Harbin continued to grow under Russian influence, until Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1932 interrupted that trajectory. This layered history explains one of the two things the city is most recognized for today: its unmistakable Russian-style architecture.

The other defining feature of Harbin is winter itself. Since 1985, the city has hosted the Ice and Snow Festival each year from late December through late February, transforming the cold into spectacle. During these months, temperatures rarely rise above –10 °C even at midday, and often fall below –30 °C at night—conditions that allow massive ice and snow sculptures to endure for weeks at a time. It was under this deep winter sky that I planned a three-day photo trip to this “Oriental Moscow” in January 2026, hoping to photograph both its Russian-influenced architecture and the monumental frozen structures of the festival.

Preparing for Architecture Photography

My usual travel camera has been the Sony A6400. Over time, however, it has proven to be less reliable in cold conditions. I have experienced freezing and malfunctions even at relatively mild temperatures around –5 °C, and the NP-FW50 battery it uses performs especially poorly once the temperature drops.

For a winter trip like this, reliability mattered more than familiarity. I chose to bring the Pentax K-70 instead—one of the smallest DSLR bodies available, yet known for its resilience in harsh environments. To photograph large buildings and ice structures, I packed the Pentax 12–24mm F4. For more general compositions and detail shots, I brought the Pentax 18–135mm F3.5–5.6. I also slipped the Pentax SMC 21mm F3.2 Limited pancake lens into the bag, in case the trip shifted away from architecture and toward street photography.

From the Airport to Zhongyang Street

Arrival at Harbin Taiping International Airport was smooth and uncomplicated. Immigration and customs moved quickly, helped by the fact that all required entry forms had been completed online in advance. Harbin receives relatively few international flights, and most airport facilities are concentrated in the domestic terminal, reached by a short walk. From there, I took the airport bus toward Zhongyang Street—a slightly bumpy ride that took about thirty minutes.

I stayed at ibis Harbin Central Street Airport Bus Station Hotel, conveniently located at the starting point of Zhongyang Street and directly across from the bus stop. The hotel staff did not speak English, but check-in was straightforward using the PDF reservation provided by Trip.com, which listed the details in both English and Chinese. The room was clean, warmly heated, and comfortable—an important detail in Harbin’s winter—though the Wi-Fi was somewhat unstable.

When Architecture Became a Crowd

After a short rest, I set out for my first photo walk in Harbin. It was a little after 4 p.m. when I stepped out of the hotel, yet the sun had already disappeared and the sky was pitch black. The weather forecast had predicted hazy conditions throughout my stay, and sure enough, there would be no blue-hour photographs that evening.

My destination was Zhongyang Street, though it quickly became clear that it was poorly suited for architectural photography. While the buildings are old and neoclassical, the area is heavily commercialized, crowded with modern signage and constant movement. The street itself is narrow and packed with tourists from all over China. Using a tripod was out of the question for safety reasons, and although decorative lights and trees add to the festive atmosphere, they also obscure much of the architecture behind them.

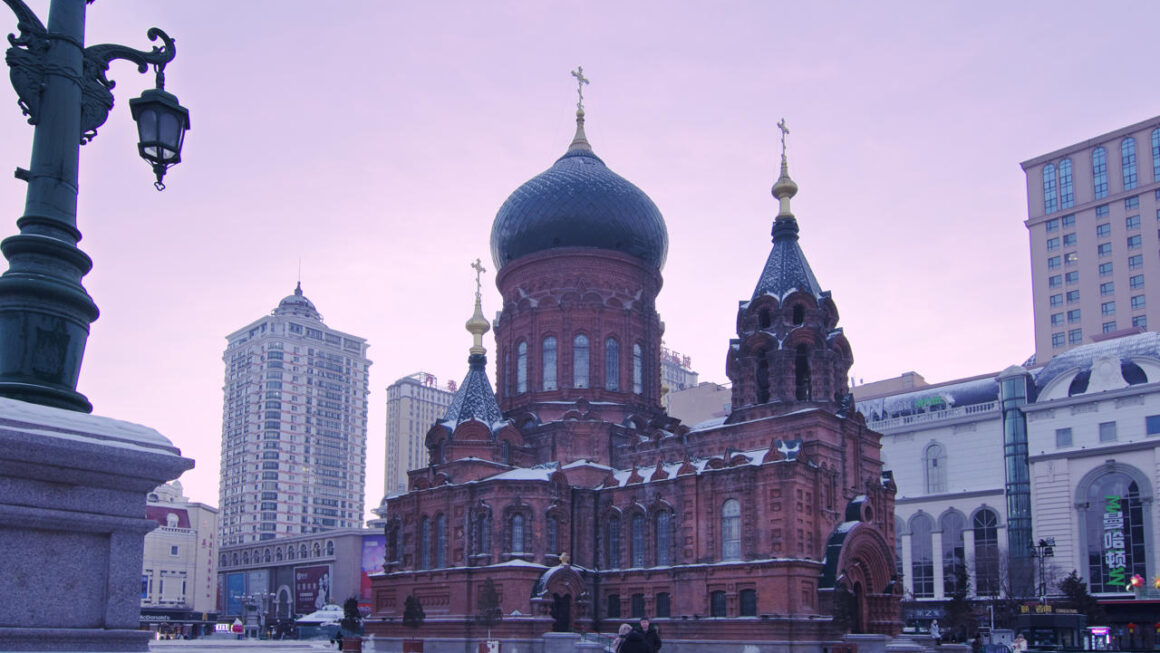

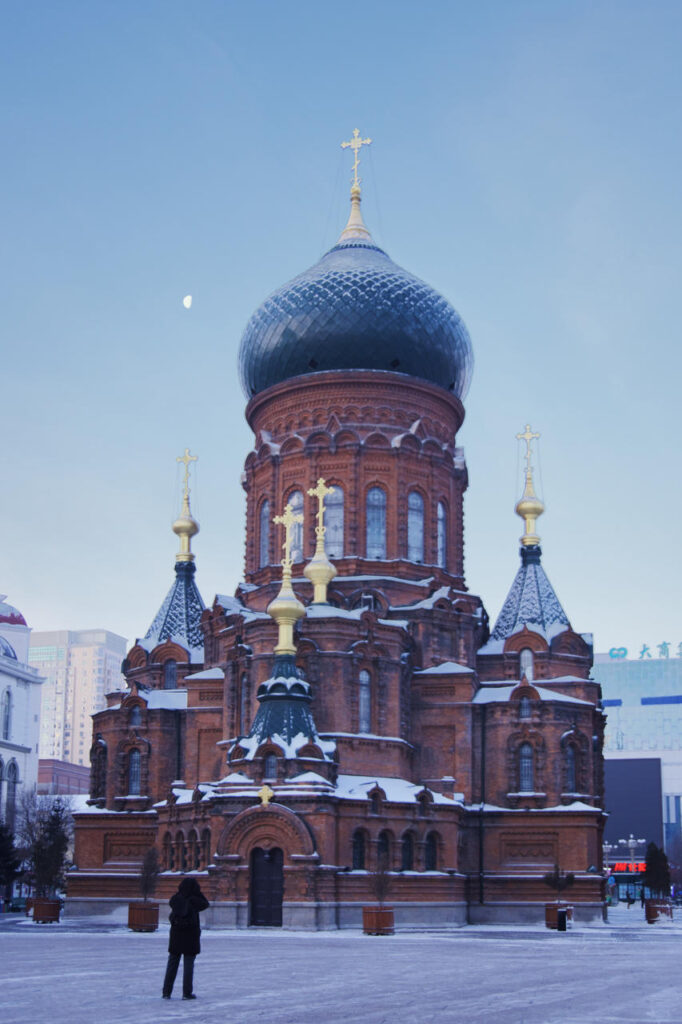

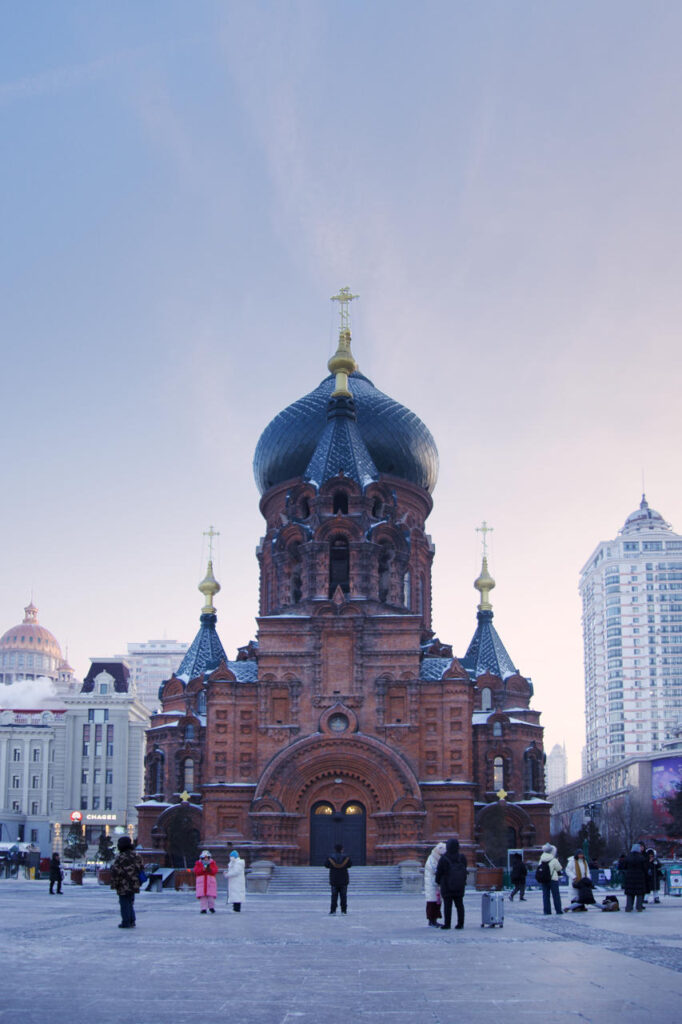

There was one photograph I truly hoped to make on this trip—Saint Sophia Cathedral. I abandoned my walk along Zhongyang Street and headed toward the cathedral to scout the area. To my surprise, it was even more crowded than Zhongyang Street itself, with cosplayers posing in front of the church. I think I saw more cosplayers there than at Anime Game Festival Korea.

Fatigue set in quickly. Rather than continuing a photo walk, I chose to simply walk and take in the festival atmosphere. Heading north along the main road, I reached the Songhua River. Along the riverbank, a vast ice and snow theme park stretched for what seemed like several kilometers, filled with snow sleds and ice slides. Standing there, my only thought was how much I wished my ten-year-old daughter were with me to enjoy it all.

Photographing Saint Sophia Cathedral Before the Crowds

The next morning, just before 7 a.m., I headed out to Saint Sophia Cathedral, this time not to scout, but to make a photograph. Based on my calculations, the light on the cathedral is better at dusk, but knowing the area would be crowded in the afternoon, I chose to work with the morning light instead.

When I arrived, there were no cosplayers, but about two dozen tourists were already present—along with roughly a dozen TikTok creators livestreaming from one side of the square. It wasn’t the livestreamers themselves that surprised me, but the realization that, somewhere in China, people were watching live TikTok broadcasts being streamed from in front of Saint Sophia Cathedral at such an early hour.

Weaving through the tourists and doing my best not to interfere with the livestreams, I spent about thirty minutes trying to capture what I hoped would be the best photograph of the trip. The sky was hazy and the light far from ideal, but this was my best opportunity. The final image wasn’t entirely satisfying, but the experience itself—learning to adapt to the conditions—felt worthwhile.

Walking Through History

To Koreans, Harbin Railway Station is a familiar place, and it became my next destination. It is where Ahn Jung-geun, a general of the Korean Independence Army, assassinated Ito Hirobumi, the first prime minister of the Empire of Japan. The incident is widely remembered for helping draw international attention to Japan’s colonial rule and for strengthening support among Allied leaders for Korea’s independence after World War II, despite Japan’s lobbying against it.

After visiting the station and the Ahn Jung-geun memorial hall inside, I spent some time walking around the area, hoping to photograph Harbin’s modern high-rise buildings. That attempt proved unsuccessful, largely due to a lack of prior research. I then took the subway to visit Jile Si, hoping to photograph a Chinese Buddhist temple, before continuing on to the Daowai Distrcit to photograph Chinese Baroque architecture. Despite its distinct architectural style, Daowai District felt similar to Zhongyang Street—heavily commercialized, with narrow streets and constant foot traffic—which made it equally difficult to approach as a subject for architectural photography.

My next plan was to visit two buildings designed by MAD Architects: the Harbin Grand Theatre and the Wood Sculpture Museum. By the time I arrived at the theatre, both my iPhone battery and my 10,000 mAh power bank were nearly depleted. After taking a few shots—which might have been golden-hour photographs if not for the clouds—I decided to retreat to the hotel to rest. That evening would be dedicated to the ice and snow sculptures, and it felt best to save my energy for what lay ahead.

Ice, Snow, and Scale

The Ice and Snow Festival unfolds across the city of Harbin, but the main stage for its largest sculptures is Ice and Snow World. As with many large venues in China, entry involves bag checks and passport checks. The admission ticket is also substantial—328 CNY for one adult. I hesitated at first because of the price, but once I stepped inside, I quickly understood why it was set so high.

The place was nothing like I had imagined. The name Ice and Snow World fits perfectly—it is a vast winter theme park. Beyond the monumental ice and snow sculptures, some rising to what looked like the height of a ten-story building, there were 500-meter-long ice slides, winter sports areas, a giant Ferris wheel, and two outdoor concert halls. It took me a couple of hours simply to walk around and grasp the scale of the place. Later, I learned that the entire site is more than twice the size of Tokyo Disneyland.

In the end, the ice and snow sculptures themselves were not the sole focus. They existed to create atmosphere. Ice and Snow World is, above all, a theme park—and perhaps the least suitable place to be alone with a camera and a tripod. I kept my camera in the bag, took in the experience, and made good use of my now fully charged iPhone to capture memories of the trip, mostly in the form of selfies.

Leaving Harbin and Trusting the Pentax K-70

I woke up late the next morning, around 9 a.m., and returned to Zhongyang Street to try the street food I had missed earlier and pick up a few gifts for my family. Getting to the airport from the hotel was simple—an airport bus stop sat just ten meters from the hotel’s front door. I boarded the bus, paid the 20 CNY fare in cash—oddly, cash was the only accepted payment—and got off at the airport’s first terminal. I couldn’t locate the international terminal at first, but with the help of a translation app and a kind bus driver, I eventually found my way.

On the flight home, I reflected on the trip. Harbin is a city with a distinct architectural character, but it does not easily lend itself to architectural photography. It is, above all, a tourist city—one better suited for shared experiences than for quiet, deliberate image-making. Next year, I hope to return with my daughter. If I do, I suspect I will come home with many more photographs, though likely of her smiles rather than of architecture.

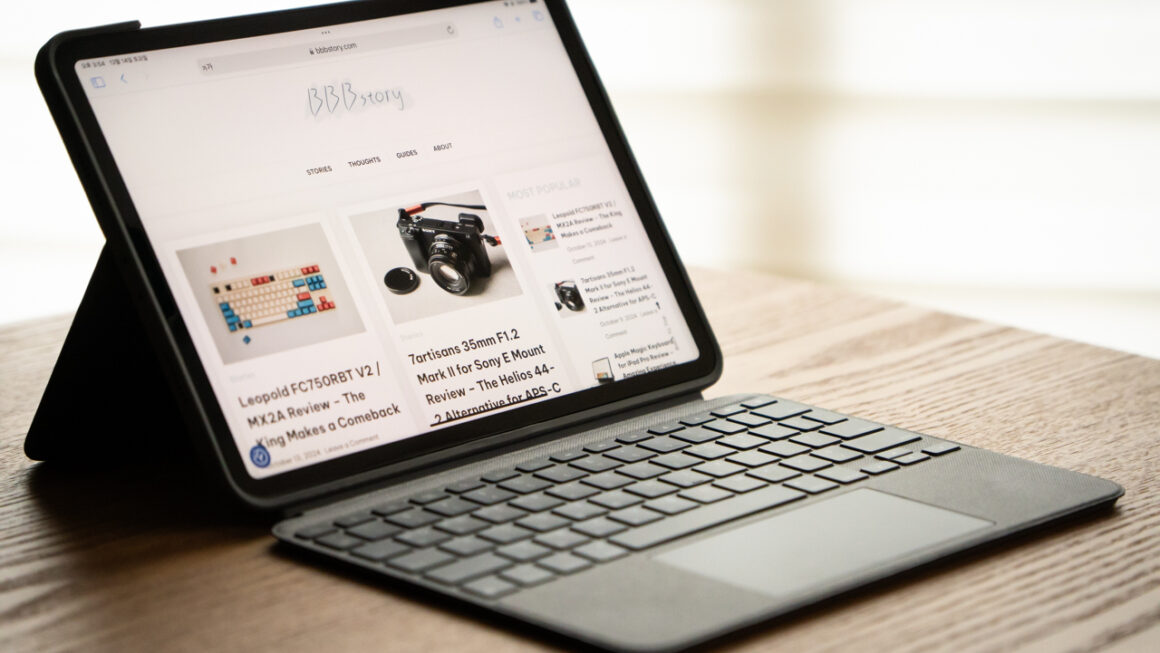

As for the camera, I would bring the Pentax K-70 again without hesitation. I never treated it gently, yet it proved worthy of the Pentax name. Despite carrying it on my shoulder for hours in temperatures around –20 °C and taking a couple hundred photographs, the original battery still showed more than 80 percent remaining when I returned home. One small limitation was that I kept the LCD screen folded in, which meant I had to rely entirely on the viewfinder to check my settings. In those conditions, a top LCD would have been welcome.

This post was created with support from ChatGPT for research, writing, and planning.